The Call of Perseus

By Hal Rocha

[ Note: A Spanish version of this article has been published this morning in La Prensa and is available at: www.laprensa.com.ni/archivo/2009/mayo/22/noticias/opinion/328444.shtml ]

In his opinion piece The Sight of the Medusa, published in his blog (www.sergioramirez.com) and reproduced in several press and literary sites throughout the Web, Nicaraguan writer Sergio Ramirez, with his ever-incisive optics, tells us about an interesting philosophical and generational statement made recently at a writers’ panel held during the Pen Club Literary Festival in New York City. According to Dr. Ramirez, Peruvian writer Santiago Roncagliolo (Lima, 1975) who, at 33 years of age has already been awarded the Alfaguara Prize for his novel Red April, said that “the eagerness to distance [our]selves from the constant of public history which trapped the forefathers with all of its abnormalities and excesses” is a fundamental difference of the new generations of Latin American writers.

I did not attend the panel in New York City, but I have read two novels by Mr. Roncagliolo and have personally heard him speak at literary fora in Madrid. I fully agree with Dr. Ramirez’s assertion that instead of freeing themselves from public history, the newer generations of Latin American artists and writers continue to work within it. Thus we return to the Hegelian and post-Kantian conception of history and the self, which invite us to rethink the dichotomy of opposites from a radically-different perspective in order to approach full freedom and truth. For Hegel truth is not fixed; it follows history’s own motion. Hence philosophy as well as intellectual, artistic, and literary pursuits must follow those same dynamics and show us how the concepts with which we think, create, and write, are transformed, from that new angle, into history itself.

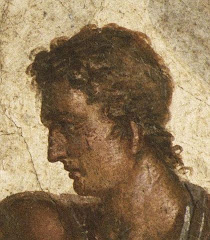

Therefore, as Dr. Ramirez argues, young Latin American artists and writers are not able to say, for now, that their work has freed itself from public history. They continue to be petrified before its Medusean eyes because they continue to address themes such as enlightened tyrannies, uncouth dictatorships, repression, corruption, and above all, that unlimited power which causes deaths, imprisonments, exiles, and seizures. As Dr. Ramirez states, “Without the presence of power, there would be no Latin American novel.” That ferrous clasp of public history seems to be the mere essence of Latin American literary works of yesterday and today. We believe we are freeing ourselves from history, but we are really simply returning to it.

It is thus possible that Mr. Roncagliolo’s statement was not intended to affirm definition-identification-recognition, but might be, instead, a generational challenge, something akin to a call upon his colleagues to search for a new direction, a new literary and artistic identity for Latin America. To achieve that, Mr. Roncagliolo, not unlike Perseus, knows he cannot look directly into the eyes of the Medusa. With the help of Hermes and Athena, this time in the form of new technologies which, among other things, kindle the illusion of overcoming time and geography; materiality and visibility; identity and history; will our Peruvian Perseus have a chance to defeat her, foregoing that lethal stare and preserving his creative freedom forever. As Dr. Ramirez states, the Medusa of public history will continue to petrify us, indeed, until Perseus carries out his call: the Call of Perseus.

For now it seems he is just thinking about it.

Madrid, May 14, 2009

© 2009, All rights reserved, including English translation

.jpg)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario